Generative AI for Busy Workers

When is it worth the effort?

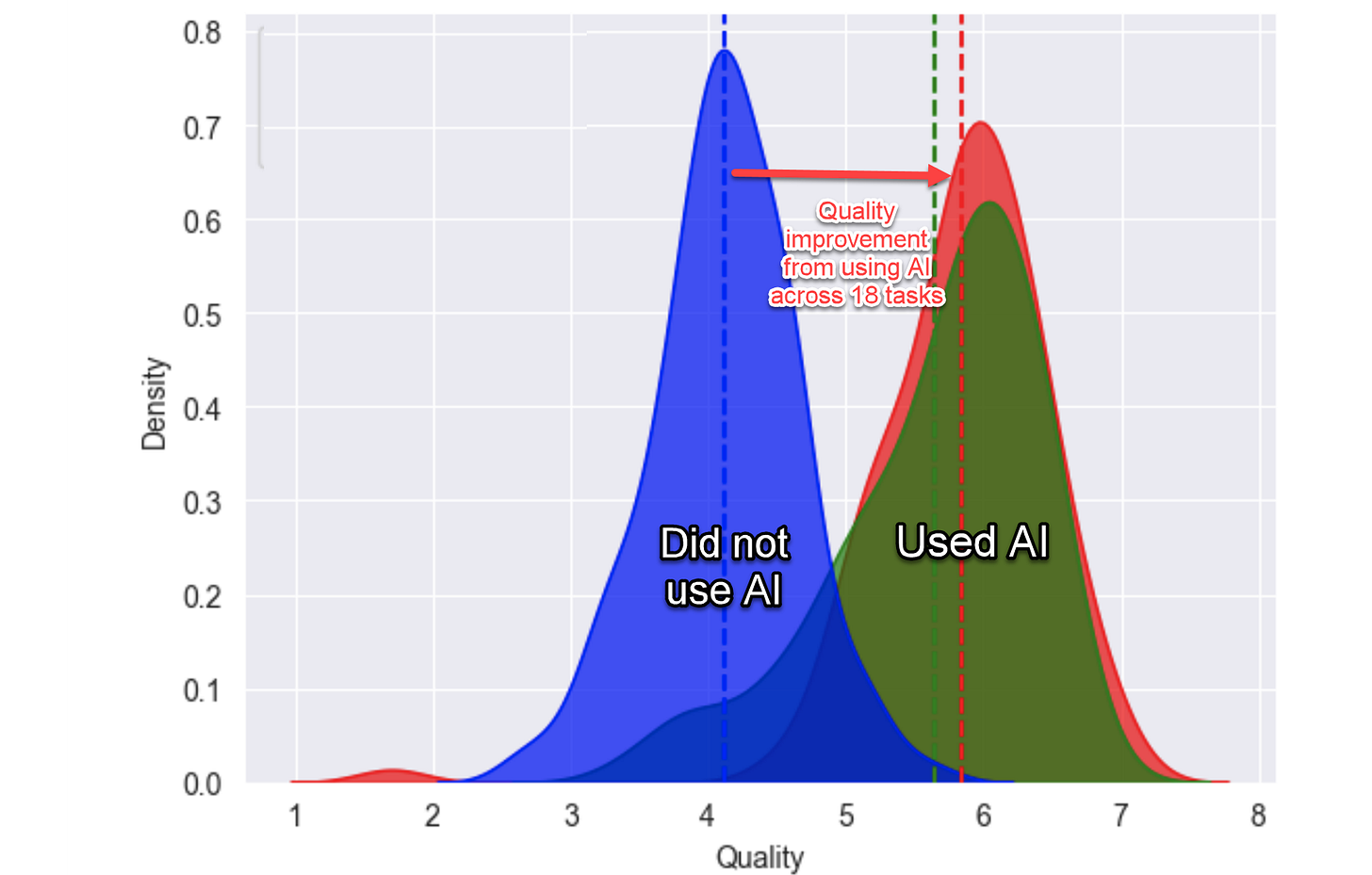

Soon after the release of ChatGPT and other Large Language Models, several studies showed that Generative AI (GenAI) systems had the potential to boost worker productivity significantly. Below is a graph I shared with you previously from a comprehensive academic study showing the shift in productivity between when workers were not using generative AI and when they were using GenAI. Similar studies in other fields showed similar results and pointed to sizable productivity gains.

However, these were academic studies with controls, validated measures of productivity, and an experimental method that incentivized the participants to do the tasks they were given. The researchers didn't give all the workers in a company a new ChapGPT account and observe their behavior from behind the copy machine. These studies were not based on observational data "from the field."

As such, an enormous chasm has developed between expectations and the reality of using GenAI in the workplace. While C-level executives go wild over the possibilities of massive reductions in the labor force, average workers see little use for GenAI in their day-to-day routine. A recent study found:

Nearly half (47%) of employees using AI say they have no idea how to achieve the productivity gains their employers expect, and 77% say these tools have actually decreased their productivity and added to their workload.

What is causing this gap?

Expected Utility of GenAI

No matter the work, we are all busy, and increasing demands are put on our time: more emails to respond to, meetings to attend, new projects to launch, etc. As such, we have to estimate the value of using a new tool like ChatGPT to complete our work and weigh it against the tools and methods we already know. Economists call this "the expected utility" of a new tool/method and, as economists are want to do, have developed entire frameworks and formulas around the idea of deciding if a new tool will work more efficiently than current methods.

So far, the expected utility of GenAI tools for daily work is much lower than that of completing work using our current methods. But so was the case with most technologies when they first got started. I was an early user of word processing (circa 1985) and had to use various inline marks to indicate where an indent, line space, or other formatting should go (similar to Markdown used today) . What you saw on the screen was NOT what was printed, so it took some imagination and work.

When most people looked at early word processing software, they took a hard pass and returned to their IBM Selectric. One reason I stuck with word processing was that I had not learned to type on a typewriter and had no existing process or experience to use as yardstick against which I could judge the utility of computer based word processing. I suspect this is true with GenAI as well; those just entering the workforce are more likely to adopt GenAI at work.

Technology adoption and dispersion were much slower in the 80s and 90s, allowing technology to mature before it was widely deployed. In our digitally accelerated world, technology is available to everyone, even if it is not ripe yet, leading to dramatic cycles of hype and busted expectations.

Like early word processing, GenAI still needs to mature, and you have to be a bit of a tech geek to take the time to fiddle with it so that you can get good results. For most non-technical people, GenAI in its current form is not that useful for the work before them that is due soon, or in my case, yesterday!

Speaking as a geek, I am only starting to use GenAI wisely and efficiently after nearly two years of fiddling. Most of our organizations employ people in primarily non-technical roles (at least not "computer technical"), who don’t have the time or inclination to learn such an immature system.

What we are seeing with GenAI adoption is a common issue with lots of technologies at the start, they don’t "crossing the chasm" unless they are mature enough for the average user to easily put to use.

Innovators (tinkerers) and Early Adopters (those with a specific problem to solve) are willing to jump on board and put the work into make GenAI work for them. Most others will not adopt GenAI until the expected utility is much greater. The expected utility of word processing didn't tip until the availability of the Graphical User Interface (GUI) and WYSIWYG (what you see is what you get) word processors. Something similar has to happen with GenAI, yet a lot of leaders fail to understand that GenAI is still a very immature technology.

Other factors

I think some other factors are at play with GenAI adoption in the workplace.

GenAI seems magical when you first play with it, but when you try to put it into production, you find it will not do ALL the work for a task. For writing, it might do 10-30 percent of the work, but you have to do the rest (either before or after involving ChatGPT/GenAI). So, you have to re-engineer your workflows to incorporate GenAI at the appropriate place for your task (which exacts more cost and lowers the expected value of GenAI). Different tasks have different GenAI workflows, and each user is charged with puzzling out how to use GenAI for different tasks. This task-dependent workflow problem is why we see so many AI companies that use ChatGPT in the background but provide a user interface that limits options and is designed for a single purpose.

GenAI systems can't do much "meta-cognition" or thinking about how to think regarding a task. As such, they rarely tell you they need more information or direction to complete a task or ask about your desired outcome if you are not detailed enough in your prompt. Most of the time, the computer just goes for it, which means that the user gets results that seem to vary in usefulness. Some responses are spot on, other times they are way off base.

A recent quote from Bill Gates about the need for Meta-cognition in AI. One of several he has made recently on the topic of Meta-cognition.

At the corporate level, too many C-level leaders buy into the myth that in order to be a leader, you have to be a first mover. The first to market, the first to deploy, etc. But research shows that it is often better to be a Fast Follower and not the first mover, especially when in “rough waters.”

Think Like A Scientist

Instead of deploying GenAI en masse, most organizations would be better off deploying a small team to find those processes or tasks where GenAI can be used reliably and repeatedly.

It is time to think like a scientist. Develop a hypothesis about a use case for GenAI in your organization, then test it and only when you have data that it will work well proceed to figure out how to scale it to everyone in your organization.

Next week: Where is GenAI driving productivity gains? Hint, one area involves users who are very "computer technical."

Let me know your experience and thoughts below!

My commentary may be republished online or in print under Creative Commons license CC BY-NC-ND 4.0. I ask that you edit only for style or to shorten, provide proper attribution and link to my contact information.

🛍️ Products I Make

#AlwaysbeLearning. In this case learning more about products and e-commerce.

Smiling Pendant with LED Eyes (in the style of the Def Con Jack) is available on Etsy. The instructions on how to make one yourself are posted on Instructables.

More coming soon. (Hint it lights up).

👍 Products I Recommend

Cables and Products from Rolling Square. (NOT an Affiliate link) I use the Aircard and an adhesive business card pocket to keep track of my journal and common books, and the Incharge cables to dramatically reduce the number of cables I carry. I also love their commitment to making a high quality product that are durable and sustainably.

Products a card game for workshop ideation and ice breakers (affiliate link). I use this in my workshops and classes regularly.

Great article Scott! I remember the days of early word processors and spreadsheets.

I appreciate your thoughts and love the idea of being a fast follower makes complete sense. Let others live on the bleeding edge. Learn from them and reduce the pain.

Brian